Jesus Takes to the Road—Again!

Jesus Takes to the Road—Again!

We are in Lectionary Year A. We are reading mostly from the gospels of Matthew and John. This week’s gospel lesson is from Luke. The reason: the account of this early appearance of the Risen Lord is an important part of the Resurrection narrative, but it is found only in Luke.

This appearance predates last week’s gospel—the appearance of the Risen Lord to the disciple, Thomas.

The travelers on the road to Emmaus have just left Jerusalem. (They were getting out of Dodge.)

It is still the third day. The news of Jesus’ Resurrection is fresh, and remember—Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead only days before. It is all a puzzle—a frightening puzzle.

The sun has yet to set on this first Easter. Cleopas and friend head in the opposite direction from the action.

You can run but you can’t hide.

Normally this hike might take two or three hours but they are probably high-tailing it.

They are troubled and discussing what had happened.

They had probably been in Jerusalem for the Passover. They may have been part of the Palm Sunday crowd. They may have witnessed some or even all of the trial, torture and crucifixion of Jesus. Perhaps they had cried for Barabbas.

The news of Jesus Resurrection comes to them as they are crushed with sorrow and perhaps guilt. If Jesus was alive, what would He think of the crowd of people who allowed Him to suffer?

They had hoped that this Jesus was the Messiah. Now they weren’t so sure. These disciples may have been doubting their own judgment or hiding their own culpability.

The news was confusing—disheartening.

Enter a stranger. Why not invite him to join them? Safety in numbers.

Imagine how the conversation might have gone. They probably spent some time scoping out the stranger. What did he know? How could he not know?

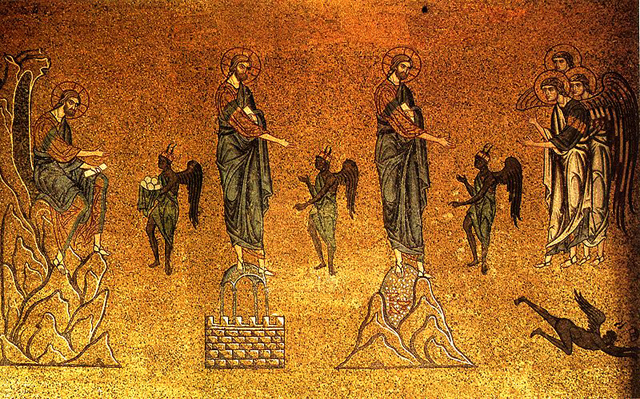

It is clear from the scripture that Jesus takes control of the conversation early on. They walk. Jesus explains.

In the end, they are trusting enough that they invite the stranger to spend the night—or did they want to keep an eye on Him?

The revelation comes with the breaking of bread—the sign—even today—of God’s presence among us.

The account of the Jesus’ appearance on the road to Emmaus, His revelation over dinner, and His sudden disappearance before the dishes were washed and put away is a favorite topic for artists. It became particularly popular in the mid 16th and 17th centuries when artists began to focus on domestic scenes, especially kitchen scenes and still life art in general.

An amazing part of this story is the long-standing assumption that both travelers were men. Luke leaves out this detail. One is named Cleopas. We know nothing about Traveler Number 2. And yet virtually all depictions show two men encountering Christ along the road.

Some modern scholars make the argument that the fact that one traveler is named and the other is not is evidence that the second traveler may very well have been female.

Is it so hard to imagine that these pilgrims visiting Jerusalem for the holidays might be husband and wife? That the invitation to enter their home was issued by the woman who would be setting the dinner table and preparing the food?

For 2000 years, we accept the prejudices of artists and we see two men traveling and sitting at the table with the stranger.

Perhaps that is why the portrayal of this scene by Diego Velázquez is so intriguing. We see the scene from the kitchen. The three travelers are talking at the dinner table in the background—but wait—only two of them are visible. A woman of color is preparing the food. Just look at her face to read her story. Is she the second traveler? Is she a servant? Velazquez intended that we see her as a maid, but that can’t stop us from imagining!

What is she is thinking?

Perhaps she returns to the table. And then the stranger disappears.

What would you do? What do Cleopas and his significant other do?

They head back to Jerusalem. Suddenly, they want to be where the action is!