Can the Church Lead the Discussion on Racial Issues?

A nearby suburban church posted a sign on their property. Three words. You’ve heard them before.

A nearby suburban church posted a sign on their property. Three words. You’ve heard them before.

People saw the sign. Some were outraged.

The three simple words seem harmless enough. The terse message leaves enough room for people to draw unintended conclusions—not necessarily the same conclusions. Some felt personally criticized. Some felt the sign was disrespectful to law enforcement.

It might just be that the sign linked them to issues they thought they had escaped.

Race is a sensitive issue! And complicated. And difficult to recognize close to home.

The pastor wrote a letter to the editor of the local paper apologizing and inviting conversation.

This raises a question. Is the Church in a position to lead this discussion? Our record for dealing with racial issues and ministering in inclusive ways is not olympian by any means!

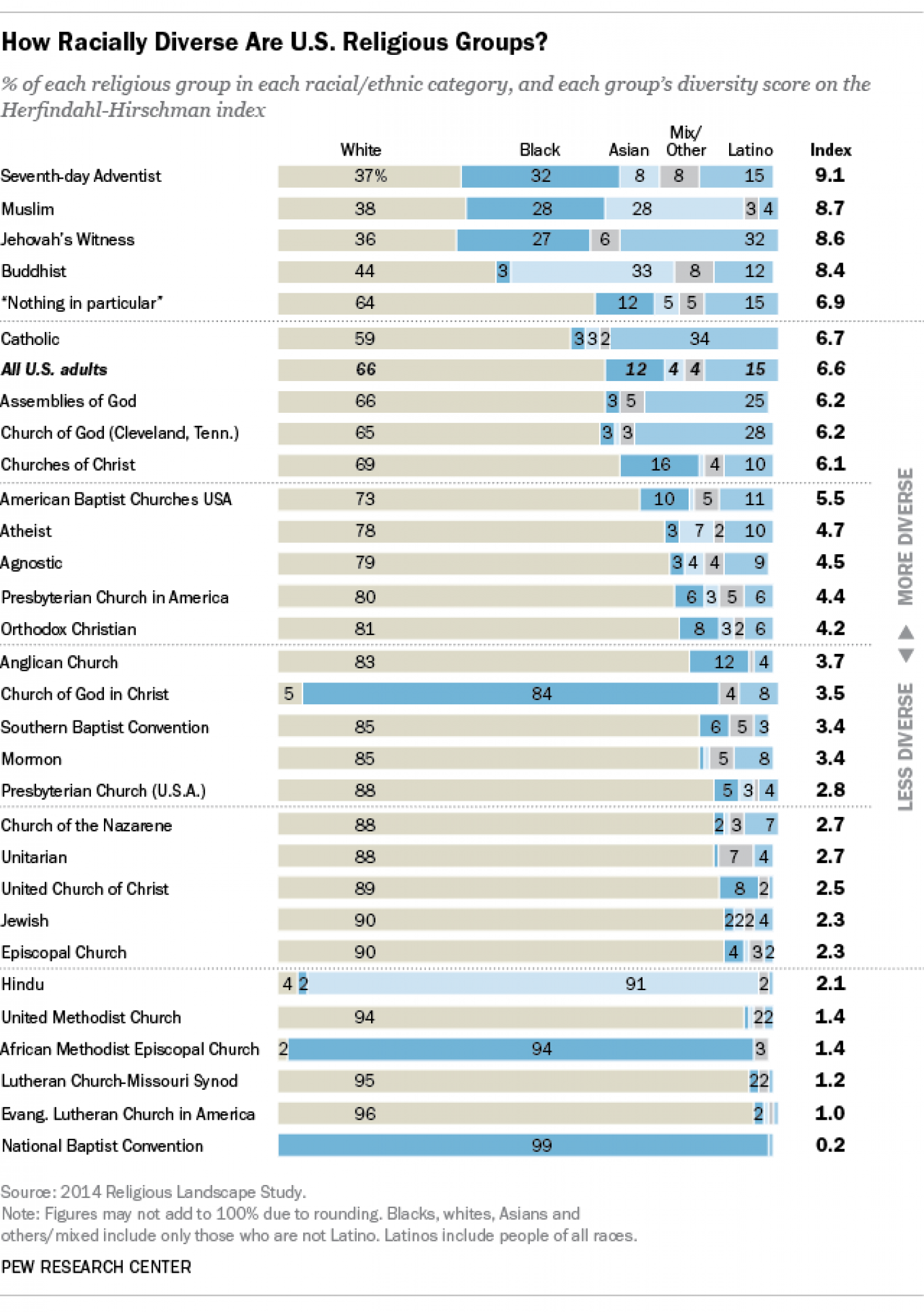

The ELCA is at the lowest rung among predominantly white denominations on inclusion. We are 96% white and the 2% that is black is largely living in some ecclesiastic version of Separate but Equal. The rest of society faced this inequality long ago!

Our congregation’s experience with the ELCA and race has been horrific and can illustrate many of the shortcomings Lutheran leadership probably doesn’t recognize.

Taking the Pollyanna View

One obstacle is the tendency to assume that leaders automatically make wise decisions. Leaders can stand in the pulpit, high above the people, and propose remedies that are based on NO experience actually dealing with the challenges and blessings of racial diversity. Most Lutherans who reach regional and national leadership positions get elected because of the name recognition that comes from serving larger churches. White Lutherandom!

Did they live close to the crime that resulted from the government-sponsored high-rise housing projects that imported and isolated new populations in neighborhoods almost overnight? Did their children attend public schools dealing with sudden, widespread change with little time to prepare and poor funding.

Yet many Lutheran laity remained in urban neighborhoods, dedicated to trying, with little voice within the denomination and inadequate professional leadership. Our needs were not a priority and were ignored for decades.

The Prejudice Created by White Flight

I was in junior high school in 1968 when streets in cities across America erupted in violence following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

White Flight began. Many Lutherans pursued happiness and hoped to find it in the suburbs. There is nothing wrong with people seeking better lives, but can suburban congregations now lead discussion on issues they left behind?

I went the opposite direction. I left a 100% white village in coal-mining, steel-producing western Pennsylvania and moved to Philadelphia, where I stayed for 35 years. The first neighborhood I lived in was Southwark—a predominantly low-income, black neighborhood. I moved to East Falls, a changing working class neighborhood within a year. (The headquarters of the Lutheran Church in America were here. Ironically, the pastors who worked there and lived in our neighborhood attended churches in other neighborhoods.)

The worst aspects of White Flight happened long after early waves of departure. I believe they are still happening today.

A friend of mine from Philadelphia’s Black Catholic community speaks with bitterness of how the Catholic Church targeted black congregations for closure, favoring neighborhoods with white members. The properties in the black neighborhoods were sold to benefit the diocese.

The same thing is happening within the ELCA.

Suburban churches became comfortable places to serve. It wasn’t long before urban congregations had to make do with retired or part-time pastors.

“Changing Demographics” Is A Racist Euphemism

Most urban neighborhoods remained well-populated, but the faces are darker and the languages spoken are not English.

Instead of seeing this societal change as an opportunity to spread our denomination’s influence (mission), the strategy of Church leaders was to mark time. Be kind to congregations as they waited for death (anti-mission). Invest nothing; do nothing to reach changed demographics. The message from the Church is clear. Black and brown lives do not matter as much as white lives.

Little effort was put into mission. Pastors continued to be trained to serve the congregations that resembled the past—suburban congregations. Laity had a better grasp of what was going on in their neighborhoods but had no voice. As things worsen, Church Consultants are called in to prepare the congregation for doom. The congregation will be required to pay the hefty consulting fees, but the consultants will report to the regional body. They’ll talk with the congregation to gain support for their fore-drawn conclusion. They will issue a report that cites “changing demographics,” referencing for $1000 or more the census statistics that are available to anyone for free. They will officially recommend and validate closure, the only plan all along.

Mission requires vision. Dollars cloud vision. Serving changing demographics is work many denominations are ill-prepared to take on.

Regional Bodies Abandon Changing Neighborhoods

This published strategy is taught to regional leaders (Transforming Regional Bodies): Triage the congregations. Provide only palliative care to the smallest. Assist them in dying.

This last step creates legal challenges. Lutheran congregations are allowed to disperse their assets to qualified organizations as they choose. But regional ELCA leaders devised methods to make sure they had first and exclusive dibs. They require congregations to accept mission status in order to receive any services from their regional body. Mission church property goes to the synod. If the congregation realizes this, things can get nasty. Other Lutherans benefit from seized assets of other churches and have incentive to look the other way. Guns are not needed when unfettered power can do the same damage.

Our bishop made an outrageous suggestion when we started to successfully reach our changing demographics. She saw ten years of neglect going down the drain. We were growing when we were supposed to be dying! They were counting on our endowment and property saving their deficit budget.

She, a coauthor of the book referenced above, asked a retired pastor and member of our congregation to lead black members of our congregation to a church she identified as a place where they “would better fit in.” When the congregation learned this, one of our black members shared that a synod representative had approached him ten years before with the same suggestion. Our black members were treated as if they were not able to choose their own faith community—twice in ten years. This is not a mistake. It’s a serious character flaw.

Why did SEPA take this action? It wasn’t direct hatred of black people. Neither was slavery. Hatred comes when a once-reliable power system breaks down. Racism is usually rooted in politics and economics. In early America, rich land owners needed cheap labor. In the Church, regional bodies can no longer depend on offerings. They covet land and endowments. There is a constitutional provision that gives the bishop the right to interfere in a congregation’s mission if the membership is scattered or diminished. She and SEPA needed our numbers to be diminished to justify seizing property and bank accounts. So our bishop attempted to orchestrate the exodus of 60+ black members. In fact, even though they never left, the report given to the Synod Assembly excluded them!

Interestingly, the approach is about making the regional body strong—not making congregations strong. Regional bodies exist to serve congregations. Topsy turvy thinking!

Dollars matter more than lives: black or white!

The Theology of Squandering Urban Assets

Many a congregation’s assets were squandered on years of salaries paid to clergy who had no intention of doing any more than caring for existing members and preaching to dwindling numbers on Sunday morning. I’ve heard seminary leaders refer to these congregations as “on life support.” The pastors serving them are called “caretaker” pastors. Some leaders even jokingly call them “undertaker” pastors. Congregations aren’t in on the jokes. They think they are paying for the real deal—pastors who will lead them into the future. They might take matters into their own hands if they learn they are paying for planned failure.

A theology was created to justify the approach. The Resurrection Story is routinely cited as justification. Resulting strategies are not biblical! They will insist that the existing congregation close. They’ll make members feel like they weren’t good enough—like their lives don’t matter. This serves an unstated purpose—gaining rights to property and control of bank accounts. They might try to reopen the church under their management, but they are likely to fail and more likely to not try at all. The practice perverts the Resurrection Story. Jesus died so that we can live.

A theology was created to justify the approach. The Resurrection Story is routinely cited as justification. Resulting strategies are not biblical! They will insist that the existing congregation close. They’ll make members feel like they weren’t good enough—like their lives don’t matter. This serves an unstated purpose—gaining rights to property and control of bank accounts. They might try to reopen the church under their management, but they are likely to fail and more likely to not try at all. The practice perverts the Resurrection Story. Jesus died so that we can live.

The ELCA should study these strategies to determine if they have any mission value that is sustainable.

Play the Race Card

Ironically, church leaders play the race card. It has emotional power and emotions are valuable when reason needs to be avoided! Much of this will take place without the knowledge of the congregation. Pastors gossip about the congregations they are eyeing for closure. No one will ask questions if they violate constitutions while fighting racism! This pamphlet describes our experience. Congregations that are called racist can expect harsh treatment, whether or not the charges are true. In our case 160 congregations including at least 200 clergy followed leaders without question. Only one congregation voted with the constitution. They left the ELCA shortly afterwards. They were as small or smaller than Redeemer. They were mostly white. They left with their property.

Racism and hatred go hand in hand.

Perhaps the Church should listen and conduct some serious self-examination before trying to lead others?