Lone Rangers Often Fail, Expert Says

But Our Eyes Keep Looking to the Horizon for the Masked Rider

But Our Eyes Keep Looking to the Horizon for the Masked Rider

The consultant author of this post, David Brubaker, writes that congregations struggling with change (in other words, all congregations) often look for a dynamic leader who can turn things around. The benefits, he explains, are often short-term and over the course of five years can do more damage than good.

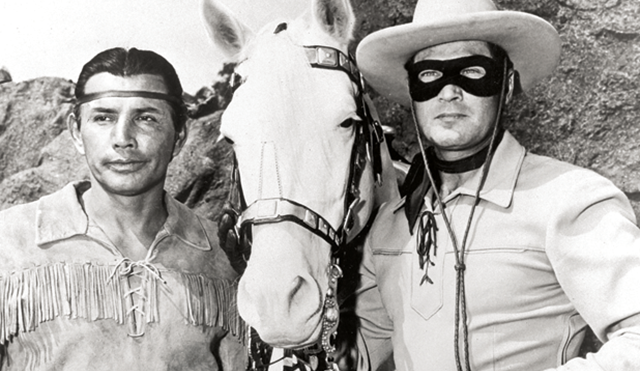

He calls it Lone Ranger leadership. (It’s probably misnamed. More about that later.)

What Brubaker describes as Lone Ranger leadership is exactly the model that is promoted by regional leadership. They even send their own Lone Ranger in. They call it an Interim Pastor. The Interim Pastor is supposed to turn things around or at least head things in the right direction before riding off into the sunset.

Congregations are expected to call a pastor not only as spiritual leader and resident theologian but also as chief executive officer. It is an unwritten rule of church leadership, a carryover from the centuries we spent in the Middle Ages. We thought we left this behind somewhere in the last 500 years of Reformation, but we keep reverting. The pastor is the boss.

Consultant Brubaker is right. This doesn’t work. Consultants aren’t likely to say so (it would be biting the hand that feeds) but the pastor as CEO may be the root of church decline.

If you read congregational constitutions, you will find that it isn’t meant to work. Most church constitutions (at least in the Lutheran tradition) assign most leadership roles to the people.

This is as it should be. The people will outlast any single leader. They carry the mantle of the congregation’s culture into the home and community. They or their descendants will be there in the pew long after a pastor decides to move on for whatever reason.

That doesn’t mean the lay culture is always right. Nor does it mean that lay culture cannot or should not budge. Skills must be honed and updated. Procedures tweaked. Customs enhanced, if not changed. The true role of leadership is to make sure the congregation is empowered to lead—not just comply.

It all comes down to love.

A loving leader can put aside personal agenda for the good of the group and for individual’s within the group. A loving leader sees each member as more than a statistic. A loving leader applauds fledgling leadership efforts and helps without criticism when they flutter without flying.

A loving leader knows that true growth is a slow process—that those fifty new members that came as a result of an initial charismatic offering might not be in it for the long haul.

Yet every time there is a congregational change, the “search committee” will be tempted and encouraged to look for leadership that will override the local leaders—the long-haul leaders. (In Redeemer’s case, the local leaders were all but asked to leave before everyone was locked out!)

Most congregational conflict is a predictable turf war in that regard. Unless leaders —both lay and clergy— adopt the biblical model of humility in a search for justice, mercy and compassion.

But let’s get back to the Lone Ranger. He —with Tonto— rode into help at the sign of trouble. He empowered the people he helped. He provided the help they needed—no more than that. He didn’t look for credit or reward. That silver bullet he left behind was a way of saying, “Glad to be of service. Now you can do it. Take it from here!”