Idea: Small Church Summit

I’ve written about this before, but the more I study modern marketing (evangelism) and business strategy, the more I am convinced that the Church is its own worst enemy.

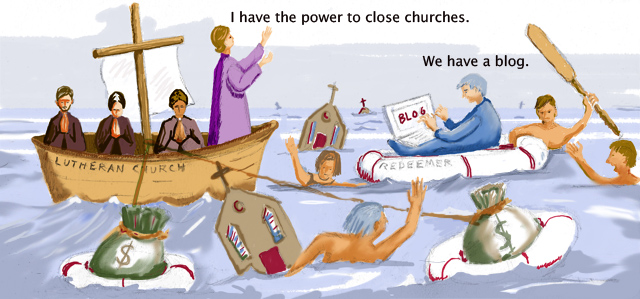

Church structure is ill-equipped to change with the modern world. Its inability to adapt is dooming congregations—all congregations—not just the small ones.

Church leadership, trained and steeped in tradition, is not leading us into the modern world. They are aware of the needs. Desperately aware.

Experts write and offer advice, usually based on isolated success stories that may or may not apply to other congregations. Church structure is a roadblock to implementation. Too many hurdles. Too much reliance on traditional relationships and procedures. Easier to slog along waiting for a miracle.

This week I attended a business conference. About eight related businesses took turns reviewing the goals and strategies of each of the others. Each business was spotlighted for 45 minutes. Their particular challenges were addressed in detail.

The businesses had to let down their guard. Hierarchy was leveled. Soon, ideas were flying. Good, helpful, concrete ideas. Each business walked away with a checklist of what to accomplish to grow their business over the next four business quarters.

It wasn’t an easy process. Some participants were afraid that their ideas would be stolen and that the criticism would suck the wind from their sails. But in the end all participated and they discovered that the other participants were eager to help. Their fresh viewpoints and experience with similar problems was energizing. They were directing one another to resources that might have been protected if the businesses were acting as competitors.

Soon the participants were sitting together into the evening, asking questions, probing, sharing advice.

I was left wondering . . .

Does this kind of free-flowing brainstorming and dialogue ever happen in the Church?

In the Church, all ideas and programs are funneled through the clergy. The clergy will want to retain control even when they don’t have the skills to implement the needed steps. They will also be weighing their position in the total hierarchy. Often their career goals are more important than congregational goals.

Laity are dismissed or enlisted as followers. Their career success is not at stake. They’ll take the blame for failure but have little control over processes.

Lay people can present ideas but the power to see them fulfilled is largely controlled by cooperation of people with allegiance to the status quo, tradition and turf to protect.

How often are lay people featured speakers at any church gatherings?

How do we get around this?

What if small congregations could band together? What if they could hold regular “mastermind” sessions. Each congregation could share their goals and frustrations. Each participant would help them evaluate and strategize. Each congregation would leave with a plan which both clergy and laity would be responsible for implementing before the next “mastermind” session.

Together we might be able to help each other overcome obstacles and see transformation and growth. Together we might share skills and resources.

Or do we all just keep ministering in isolated despair, waiting for the other boot to drop, wallowing in knowing what the problems are without a clue as to how to address them?

This is our proposal. It’s just a start, but it could grow into something HUGE!

One small church provide leadership initiative.

Invite five-ten other small churches to attend a “Small Church Summit” that would explore common and unique problems. The congregations don’t have to be all the same denomination. We could learn from one another!

Once problems are defined, the group can focus on each congregation. Offer ideas and support.

It’s important that clergy and laity interact. Both must attend. As equals. The Lutheran way!

What do you think? Would a Small Church Mastermind Summit interest you?

2×2 would love to develop this idea. Contact us if you have interest.